↓ Patent Schwarzlose

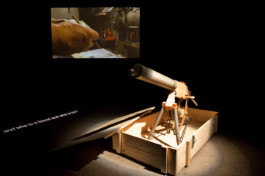

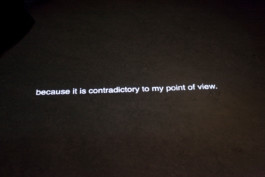

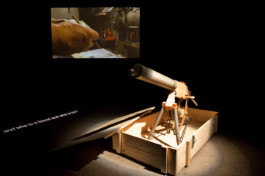

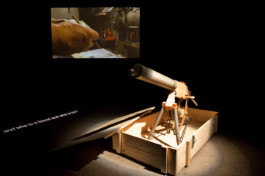

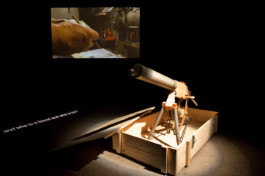

Patent Schwarzlose is an installation that combines a wooden model of a machine gun, a video projection and an audible monologue plus a translation of it, projected on the ground. Another part of the work is a publication. The work circles around a namesake of mine and his invention.

YEAR

2009

MATERIALS

Wood / video / sound / publication

Patent Schwarzlose M.07/12

"Did you ever Google our last name?" my sister asks me. I have to say no, because it has never crossed my mind to do so. “You should try it once - it's kind of mad! You will find that a guy called Schwarzlose invented a huge machine gun back in the First World War.” I am quite impressed by that finding. We both fantasize about the possibility of being related to a man like that and think the whole story is strange and funny.

When I try it myself and type my last name into the Google Search window, a link does indeed appear, leading to a Wikipedia entry: Andreas Wilhelm Schwarzlose was the inventor of one of the first machine guns; the 'Patent Schwarzlose M.07/12' - an enormous, heavy, water-cooled monster. It was used during the First and the Second World War in different European countries. The Austro Hungarian army was equipped with it, then Italian and Russian units captured and used it. It was also exported to Greece and The Netherlands. Later it was used by the Nazi German army and also against them, in Czechoslovakia. The list of countries which had the gun in service is long and it left its mark on almost all the big historic conflicts in Europe.

I visit my parents, curious to tell them about the strange news I have learned. I decide to first talk to my father. My discovery should be of interest to him, since I know about his fascination for military history and weapons. His reaction however surprises me. He knew about Schwarzlose and his invention - for a long time already. Instantly, as if he'd been waiting for this moment, he fetches two books - a weapons encyclopedia and some old army guide for soldiers. Both feature short illustrated articles on the Schwarzlose MG; it is so different from the automatic firearms we know today. In order to be operated, it had to be mounted on a tripod with an integrated seat, reminding me of a bike saddle. Several soldiers were needed to operate it. One to adjust and aim, one to feed ammunition and one to sit on the saddle and fire. Soldiers used it as an infantry weapon, the marines mounted it on their ships and it was an aircraft and anti-aircraft gun as well. From my father I also learn that Schwarzlose was even born in Wust - the same area my mother's family comes from. Talking to my mother about this subject won't be easy. I have to think of all the evenings when my father sits in a lone, throne-like armchair in the living room and watches Vietnam war movies. My mother walks in, comments on the scenario with a disapproving exhaling sound and leaves the room. This sequence exists in a number of variations, like 'Mafia drama', 'WW2 documentary', 'Western' or 'Crime Series'. My mother hates all those genres. For my father it is conflict - in all its shapes and sizes, and especially with all its historical, political and technical facts - that has a captivating effect on him. He has pointed out, more than once, that war is ugly and terrifying, but in his opinion it is necessary to know about terrifying things as well. On exactly that point my mother disagrees with him and disagrees strongly. Her approach is directly opposite: She refuses to speak about disgusting things, because they disgust her. It seems like she fears that the moment you open a terrible topic up for discussion you have already lost. You have let it into your life, you know about it and the more you understand, the greater the chance that it will corrupt you. It is the chill it gives you, when you feel your moral concepts are not rock solid, but can be shaken any moment by what you learn, that chill she wants to avoid by all means. My mother would not openly question my fathers interest, because that would force her either to reason or to argue with him about it. Both require her to track down the source of her fear and disgust. There's a fair amount of tense situations and uncomfortable scenes between the two in my memory - enough to tell me it might be sensible to drop the subject. However I decided this is not the time to be sensible. After all, it is my mother's name that my sister and I are carrying. As expected she is at first indifferent - later even repulsed, to talk or hear about the inventor of the Schwarzlose. I can try all I want, but it is impossible to get more than a sour gesture of disinterest out of her, for now anyway.

Back in Amsterdam I tell my story to a Swedish friend. He finds out that the Swedish army produced three different medals with the 'Schwarzlose Kulspruta' as a motive. He speaks to his grandfather, who remembers operating the gun, but the medal is nowhere to be found. Later we contact a Swedish militaria collector who not only sends me a medal, but also hints that he might know someone who could sell me the entire gun if I was interested. Another friend of mine from Israel knows that the Schwarzlose has been used by some units of the Israeli army as well. The soldiers gave it the Nickname 'shgorke', meaning 'Blacky'. Soon the topic is becoming unavoidable to me. My little network of absurd interconnections is growing and information starts finding me before I even look for it. Only a short while later I am approached by another acquaintance: "Say, what was your last name again ?" he asks me. He tells me how he had been to Bronbeek, a famous Dutch military museum in Arnhem. There he had seen, among other relics of Holland's colonial war in Indonesia, the Schwarzlose gun exhibited in a glass cabinet. When I contact the curator of the museum, he proudly tells me they not only have one, but two Schwarzlose mitrailleurs in their collection and he invites me to pay a visit.

The museum itself is a rather unusual place, a mixture between an elderly veterans home and a military museum, all in the same building. One would leave a room where guns and knives and other weapons are displayed and go next door, only to find a bunch of old men playing pool and drinking lemonade in an old-fashioned cafeteria. The veterans seem to be on display as living war relics, they too are part of the grand historical exhibition. As I am standing in front of the glass cabinet which contains the machine gun, looking at it and observing closely all the little bits and pieces it consists of on a large cross section map, a man enters the room. He greets me and asks for my name. As I introduce myself, his face lights up and we shake hands. He is the weapons expert of the museum. He knows the Schwarzlose mitrailleur very well and explains how it works. How many bullets it fires ( 500 per minute ), how heavy it is (machine gun: 24 kg, tripod: 20 kg), where it was manufactured (Steyr and Berlin) and why it was so popular (not for being a weapon of great accuracy or sophisticated development, but simply for being easy and cheap to produce). The man enjoys talking about all those technical and historical facts and I enjoy listening to them. “A truly marvelous piece of invention your great grandfather made.” He claps on my shoulder in approval. “Hm” I am unsure what to say. The name is all he needs. It ties me to the story of the gun whether I like it or not. If my last name was different I would not be here. The name is charged with history and it passes on its charge. Standing directly next to the gun I ask how all the weapons in the museum are deactivated, I had heard that it is illegal to possess functioning weapons of this kind since the end of the Second World War. “Oh no,” he says, “this weapon is sharp. If it wasn't, its whole history would be destroyed. That is why we have a special permit for all guns we exhibit.” “Hh - aha” again I do not have a smart answer, mainly because my Dutch is not really sufficient for a more precise discussion. I somehow don't mind my handicap. It allows me to listen and keep my thoughts to myself. The weapons expert shows me his key chain. Attached to it is a single bullet. “Do you see this? This is the ammunition which was fired with the Schwarzlose. Those bullets we made ourselves, here in Holland.” I catch myself silently speculating why he is using this bullet as a talisman...

Because I would like to take some photographs of the Schwarzlose, he insists on opening the cabinet for me and having me climb inside it. He gives me a hand as I enter the glass case and tells me it is important to get close enough. Otherwise I would miss all the important details.

↓ Patent Schwarzlose

Patent Schwarzlose is an installation that combines a wooden model of a machine gun, a video projection and an audible monologue plus a translation of it, projected on the ground. Another part of the work is a publication. The work circles around a namesake of mine and his invention.

YEAR

2009

MATERIALS

Wood / video / sound / publication

Patent Schwarzlose M.07/12

"Did you ever Google our last name?" my sister asks me. I have to say no, because it has never crossed my mind to do so. “You should try it once - it's kind of mad! You will find that a guy called Schwarzlose invented a huge machine gun back in the First World War.” I am quite impressed by that finding. We both fantasize about the possibility of being related to a man like that and think the whole story is strange and funny.

When I try it myself and type my last name into the Google Search window, a link does indeed appear, leading to a Wikipedia entry: Andreas Wilhelm Schwarzlose was the inventor of one of the first machine guns; the 'Patent Schwarzlose M.07/12' - an enormous, heavy, water-cooled monster. It was used during the First and the Second World War in different European countries. The Austro Hungarian army was equipped with it, then Italian and Russian units captured and used it. It was also exported to Greece and The Netherlands. Later it was used by the Nazi German army and also against them, in Czechoslovakia. The list of countries which had the gun in service is long and it left its mark on almost all the big historic conflicts in Europe.

I visit my parents, curious to tell them about the strange news I have learned. I decide to first talk to my father. My discovery should be of interest to him, since I know about his fascination for military history and weapons. His reaction however surprises me. He knew about Schwarzlose and his invention - for a long time already. Instantly, as if he'd been waiting for this moment, he fetches two books - a weapons encyclopedia and some old army guide for soldiers. Both feature short illustrated articles on the Schwarzlose MG; it is so different from the automatic firearms we know today. In order to be operated, it had to be mounted on a tripod with an integrated seat, reminding me of a bike saddle. Several soldiers were needed to operate it. One to adjust and aim, one to feed ammunition and one to sit on the saddle and fire. Soldiers used it as an infantry weapon, the marines mounted it on their ships and it was an aircraft and anti-aircraft gun as well. From my father I also learn that Schwarzlose was even born in Wust - the same area my mother's family comes from. Talking to my mother about this subject won't be easy. I have to think of all the evenings when my father sits in a lone, throne-like armchair in the living room and watches Vietnam war movies. My mother walks in, comments on the scenario with a disapproving exhaling sound and leaves the room. This sequence exists in a number of variations, like 'Mafia drama', 'WW2 documentary', 'Western' or 'Crime Series'. My mother hates all those genres. For my father it is conflict - in all its shapes and sizes, and especially with all its historical, political and technical facts - that has a captivating effect on him. He has pointed out, more than once, that war is ugly and terrifying, but in his opinion it is necessary to know about terrifying things as well. On exactly that point my mother disagrees with him and disagrees strongly. Her approach is directly opposite: She refuses to speak about disgusting things, because they disgust her. It seems like she fears that the moment you open a terrible topic up for discussion you have already lost. You have let it into your life, you know about it and the more you understand, the greater the chance that it will corrupt you. It is the chill it gives you, when you feel your moral concepts are not rock solid, but can be shaken any moment by what you learn, that chill she wants to avoid by all means. My mother would not openly question my fathers interest, because that would force her either to reason or to argue with him about it. Both require her to track down the source of her fear and disgust. There's a fair amount of tense situations and uncomfortable scenes between the two in my memory - enough to tell me it might be sensible to drop the subject. However I decided this is not the time to be sensible. After all, it is my mother's name that my sister and I are carrying. As expected she is at first indifferent - later even repulsed, to talk or hear about the inventor of the Schwarzlose. I can try all I want, but it is impossible to get more than a sour gesture of disinterest out of her, for now anyway.

Back in Amsterdam I tell my story to a Swedish friend. He finds out that the Swedish army produced three different medals with the 'Schwarzlose Kulspruta' as a motive. He speaks to his grandfather, who remembers operating the gun, but the medal is nowhere to be found. Later we contact a Swedish militaria collector who not only sends me a medal, but also hints that he might know someone who could sell me the entire gun if I was interested. Another friend of mine from Israel knows that the Schwarzlose has been used by some units of the Israeli army as well. The soldiers gave it the Nickname 'shgorke', meaning 'Blacky'. Soon the topic is becoming unavoidable to me. My little network of absurd interconnections is growing and information starts finding me before I even look for it. Only a short while later I am approached by another acquaintance: "Say, what was your last name again ?" he asks me. He tells me how he had been to Bronbeek, a famous Dutch military museum in Arnhem. There he had seen, among other relics of Holland's colonial war in Indonesia, the Schwarzlose gun exhibited in a glass cabinet. When I contact the curator of the museum, he proudly tells me they not only have one, but two Schwarzlose mitrailleurs in their collection and he invites me to pay a visit.

The museum itself is a rather unusual place, a mixture between an elderly veterans home and a military museum, all in the same building. One would leave a room where guns and knives and other weapons are displayed and go next door, only to find a bunch of old men playing pool and drinking lemonade in an old-fashioned cafeteria. The veterans seem to be on display as living war relics, they too are part of the grand historical exhibition. As I am standing in front of the glass cabinet which contains the machine gun, looking at it and observing closely all the little bits and pieces it consists of on a large cross section map, a man enters the room. He greets me and asks for my name. As I introduce myself, his face lights up and we shake hands. He is the weapons expert of the museum. He knows the Schwarzlose mitrailleur very well and explains how it works. How many bullets it fires ( 500 per minute ), how heavy it is (machine gun: 24 kg, tripod: 20 kg), where it was manufactured (Steyr and Berlin) and why it was so popular (not for being a weapon of great accuracy or sophisticated development, but simply for being easy and cheap to produce). The man enjoys talking about all those technical and historical facts and I enjoy listening to them. “A truly marvelous piece of invention your great grandfather made.” He claps on my shoulder in approval. “Hm” I am unsure what to say. The name is all he needs. It ties me to the story of the gun whether I like it or not. If my last name was different I would not be here. The name is charged with history and it passes on its charge. Standing directly next to the gun I ask how all the weapons in the museum are deactivated, I had heard that it is illegal to possess functioning weapons of this kind since the end of the Second World War. “Oh no,” he says, “this weapon is sharp. If it wasn't, its whole history would be destroyed. That is why we have a special permit for all guns we exhibit.” “Hh - aha” again I do not have a smart answer, mainly because my Dutch is not really sufficient for a more precise discussion. I somehow don't mind my handicap. It allows me to listen and keep my thoughts to myself. The weapons expert shows me his key chain. Attached to it is a single bullet. “Do you see this? This is the ammunition which was fired with the Schwarzlose. Those bullets we made ourselves, here in Holland.” I catch myself silently speculating why he is using this bullet as a talisman...

Because I would like to take some photographs of the Schwarzlose, he insists on opening the cabinet for me and having me climb inside it. He gives me a hand as I enter the glass case and tells me it is important to get close enough. Otherwise I would miss all the important details.