Chandigarh, Le Courbusier

In the 1950’s French-Swiss architect Le Corbusier worked on the layout for the city of Chandigarh in India. Its first city to be build after the independence from the British coloniser. Included in this masterplan was the new to be build High Court. Attracting Le Courbusier, the godfather of high Modernist architecture, would add grandeur and a sense of cosmopolitanism to the new state of India. His designs and architecture have in the meantime also become famous for the way he enforced abstracted ideas of how to live that frequently clashed with how people actually lived.

In a perverse manner the attempted overcoming of colonialism returned in Chandigarh through Le Corbusier’s designs that reenforced European ideals of proper form and conduct.

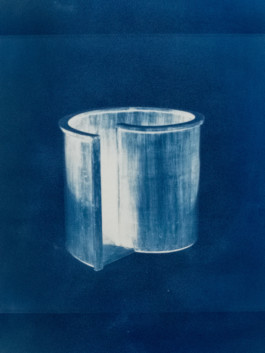

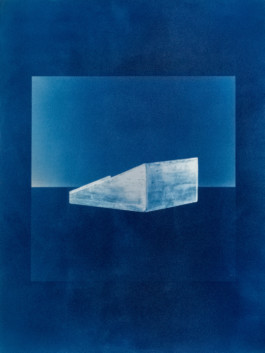

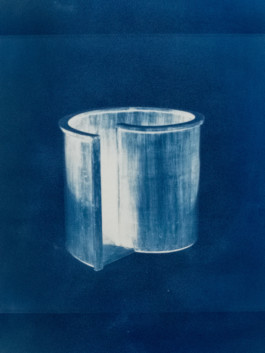

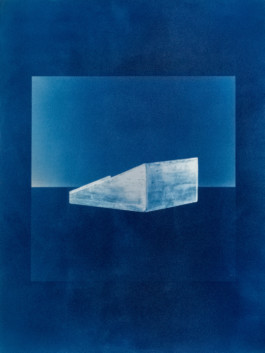

Le Corbusier implemented many of his elemental thoughts on modernist architecture to the furniture of the courthouse, or what he liked to call ‘equipment’ as to initiate a new relation to the world that he designed. Pictured here are cyanotypes of these pieces of equipment, a judge’s desk, an accused stand among others. These abstracted shapes exemplify the way abstract Western ideals of equality, proper governance and nation-building were reiterated in post-independence India.

Although Le Corbusier was also thinking about how his designs could add to a more democratic and just world, these pieces were lost/looted and recently auctioned off for large amounts of money to collectors in the Western collectors world.

Le Courbusier’s major ideological clash with the officials and judges at the Courthouse arose with the tapestries he designed for the courtrooms. The large scale cubist designs were disavowed by the judges that were working in these courts, to which Le Courbusier responded that “they should confine themselves to being judges of law, not set themselves up as judges of art”. In the decades that followed rectangular shapes were cut out of the tapestries to accommodate for the vents of the airconditioning system that was installed in the courthouse. The tapestries were later taking into conservation at the National Museum. Interestingly, despite being designed as abstracted ideals of High Modernism the tapestries started to weave a longer story of post-colonialism and the frictions that it gathered during their lifetime.

YEAR

2018

MATERIALS

Cyanotype Print, Fedrigoni 100% Cotton Paper

DIMENSIONS

60 x 80cm

Chandigarh, Le Courbusier

In the 1950’s French-Swiss architect Le Corbusier worked on the layout for the city of Chandigarh in India. Its first city to be build after the independence from the British coloniser. Included in this masterplan was the new to be build High Court. Attracting Le Courbusier, the godfather of high Modernist architecture, would add grandeur and a sense of cosmopolitanism to the new state of India. His designs and architecture have in the meantime also become famous for the way he enforced abstracted ideas of how to live that frequently clashed with how people actually lived.

In a perverse manner the attempted overcoming of colonialism returned in Chandigarh through Le Corbusier’s designs that reenforced European ideals of proper form and conduct.

Le Corbusier implemented many of his elemental thoughts on modernist architecture to the furniture of the courthouse, or what he liked to call ‘equipment’ as to initiate a new relation to the world that he designed. Pictured here are cyanotypes of these pieces of equipment, a judge’s desk, an accused stand among others. These abstracted shapes exemplify the way abstract Western ideals of equality, proper governance and nation-building were reiterated in post-independence India.

Although Le Corbusier was also thinking about how his designs could add to a more democratic and just world, these pieces were lost/looted and recently auctioned off for large amounts of money to collectors in the Western collectors world.

Le Courbusier’s major ideological clash with the officials and judges at the Courthouse arose with the tapestries he designed for the courtrooms. The large scale cubist designs were disavowed by the judges that were working in these courts, to which Le Courbusier responded that “they should confine themselves to being judges of law, not set themselves up as judges of art”. In the decades that followed rectangular shapes were cut out of the tapestries to accommodate for the vents of the airconditioning system that was installed in the courthouse. The tapestries were later taking into conservation at the National Museum. Interestingly, despite being designed as abstracted ideals of High Modernism the tapestries started to weave a longer story of post-colonialism and the frictions that it gathered during their lifetime.

YEAR

2018

MATERIALS

Cyanotype Print, Fedrigoni 100% Cotton Paper

DIMENSIONS

60 x 80cm